It can be easy to shrug off simple financial concepts such as “assets” and “liabilities.” But it is imperative to intimately understand these concepts and be able to apply them to our individual situations. Without that understanding, how will we know how much wealth we have that needs protection, or how secure we are in our future retirement plans? What is considered liquid, and what is illiquid?

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki is a classic financial self-help book that does a great job of making distinctions between assets and liabilities. Kiyosaki defines an asset as “something that puts money in your pocket.” A liability is “something that takes money out of your pocket.” The definitions are so simple they seem over-simplified. But at the core, it really is that simple.

Your stock portfolio, over the long term, will put money in your pocket if you, for example, invest in dividend paying stocks. Investing in bonds will put money in your pocket. Investing in stocks that increase in value over time, assuming you use a buy-and-hold strategy and do not sell out when the market tumbles, will put money in your pocket when you eventually do sell them for a gain.

Here is where it can get controversial. Your car is not an asset. Your home is not an asset. Those are liabilities.

Yes, those statements go against the wisdom of the general public. But they are true.

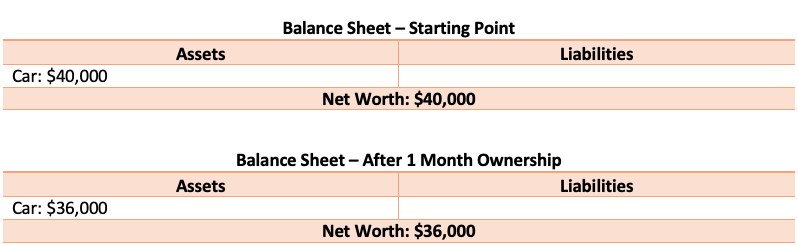

If you go buy a brand-new car, just by driving it off the car lot, it loses value. Carfax data suggests that “cars typically lose more than 10% of their value in the first month after you drive off the lot, and it keeps dropping from there.” You can put the $40,000 the car cost you in the asset column and feel better about your financial situation, but that ignores the true value. Now, one month later, the car is really worth approximately $36,000.

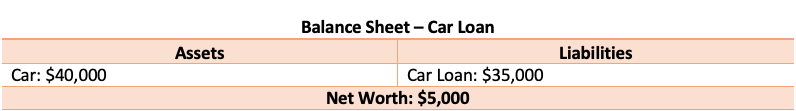

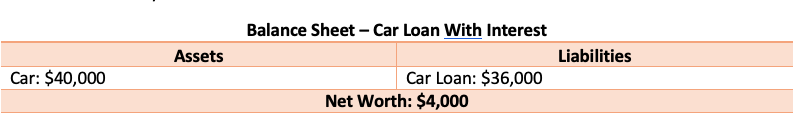

Let’s go one step further. Let’s say you took out a car loan to purchase the vehicle. You have $40,000 in your assets column for the car, and $35,000 in the liabilities column to represent the car loan. You’re feeling good about your situation because you have a net gain from this transaction, according to your balance sheet.

Interest rates are low right now, so let’s say you have a 2% interest rate on your car loan of $35,000. You’re paying it back over the course of 3 years. You’re going to end up paying about $1,000 in interest over the lifetime of your loan.

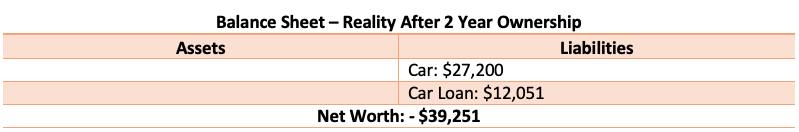

Flash forward three years in the future. You’ve paid off the car loan, and now the car is really and truly owned by you. Things are looking really good for your balance sheet, too. Now your net worth has grown because the car loan is gone, and you just have the value of the car in the asset column. But do you have the true value?

According to Carfax, at the end of the third year of ownership, your $40,000 car is really worth approximately $23,120.

Costs:

Depreciation: estimated 15% of value annually

Maintenance: $792 annually

Interest: $333 annually for 1st 3 years of ownership

Obviously, you still need a car. The point of this exercise is not to discourage you from purchasing a vehicle, but rather, to recognize it for what it is: a liability. It depreciates, and it involves a host of other costs.

Homes are another area in which the lines between assets and liabilities blur. Sure, homes tend to appreciate in value, but they do not always do so. If you bought at the peak of a housing bubble, you likely overpaid and will have a difficult time even selling the property for what you paid. Beyond that, property taxes, home maintenance, interest on a mortgage… all are costs that need to be factored in.

Homes and cars are also considered illiquid. It can take time to sell and receive a fair price. There is a lot of effort involved, from staging to hosting open houses. If you have a financial emergency and you need cash, selling your car or your home is not a good idea.

The moral of this long story is to not let yourself fall into the trap of buying too much house or too much car under the justification that it is an investment. These are all great milestones and necessities, but they are not investments. Stay within your means, and buy them for what they are: liabilities.

Recognizing the true value of your assets and liabilities is also important when looking at protection in the form of insurance.

How much life insurance do you need? Make sure to factor in the mortgage on your house and the balance on your car loan, but also those continual costs involved. Even if you pay off your mortgage, you will always have property tax and homeowner’s insurance, in addition to continual maintenance.

How much disability insurance do you need? Make sure you have enough monthly income coming in to cover those extra costs, such as maintenance and taxes. You don’t want to be in a position where you are taking losses on possessions such as your car and your home because you were forced to sell. This is also the importance of having an emergency fund, especially if you lack short-term disability insurance and your long-term disability insurance has a waiting period.

Resources:

https://www.richdad.com/what-are-assets-and-liabilities

https://www.carfax.com/blog/car-depreciation

https://www.aaa.com/autorepair/articles/what-does-it-cost-to-own-and-operate-a-car